We may never know what sounds and melodies the Greeks and Romans invented, nor what rhythms persuaded them to get up and dance. There are written records of Greek music played and sung but sadly music notation, as we know it, had not been invented so we will never be able to repeat it. Isidore of Seville wrote that “Unless sounds are held by the memory of man, they perish, because they cannot be written.”

Nowadays, we are extremely lucky that the joyous music of Beethoven can be played hundreds of years after it was written, whenever the musicians wish to, and in exactly the way that Beethoven composed it, with every nuance followed to the letter of the composer. In his final years, sadly Beethoven, because of his deafness, couldn’t hear his own works, but at least he gave the necessary notation to those who could play it and for those who could then enjoy the pleasure of it. But how did music notation come about and who thought of it?

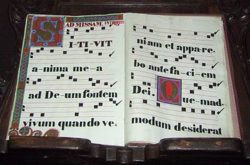

By the middle of the 9th Century, a form of notation began to develop in monasteries in Europe as a memory device for Gregorian Chant, using symbols known as neumes. A few fragments of Visigothic neumes have been discovered, but they have not yet been deciphered. Unfortunately, these were just reminders of music with which the musician was already familiar but had no detailed instructions on how to play a new piece.

Eventually, to address the issue of exact pitch, a staff was introduced, consisting originally of a single horizontal line, but gradually over time this was extended until a system of four parallel, horizontal lines was standardised which became our recognisable stave today. Although the four-line stave has remained in use until the present day for plainchant, (a religious musical prayer used by religious orders for sections of the Mass), for other types of music, staves with differing numbers of lines have been used at various times and places for various instruments. The modern five-line stave was first adopted in France and became almost universal by the 16th century (although the use of staves with other numbers of lines was still widespread well into the 17th century).

Copyright: Alex Weeks (Wikipedia)

Music today is incredibly varied and one can tell the different ethnic elements, from the instantly recognisable Spanish flamenco, Indian Bollywood music to Jazz and Blues, which stem from African music brought to America by the slaves imported to work on the cotton plantations. Each race epitomises its own culture with its own songs and its own instruments. I recall having a Finger Piano, which was played to me by an African boy when I lived in Zambia. I have since discovered it was invented 3000 years ago! Did I hear melodies that have survived and been passed down by ear from generation to generation?

And returning to notation of music…., as usual, the Chinese were not behind with their invention of the handling of music notation. The earliest known examples of text referring to music in China are inscriptions on musical instruments found in the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (d. 433 B.C.). Sets of 41 chime stones and 65 bells survive with each having long inscriptions about pitch, scales, and transposition. The bells still sound the pitches that their inscriptions refer to. For many years, music scholars in China and Japan tried unsuccessfully to decipher ancient musical notations that looked a bit like Chinese characters. They found the key to the puzzle in the city of Xi’an in northwest China, where the music is still performed by a dwindling number of orchestras. The notation was used by court musicians of the Tang Dynasty as far back as the seventh century – predating Europe’s Gregorian chants, described above, which are commonly and mistakenly described as the earliest written music.

In the seventh century, Xi’an was known as Chang’an. It was the capital of the Tang Empire and the world’s largest city, with roughly 1 million residents. Chang’an lay at the eastern end of the Silk Road, and scholars, priests and merchants from India, Japan, Persia and Byzantium created a thriving trade there in goods and ideas.

Li Kai, who leads a ‘Tang Dynasty’ music ensemble in Xi’an, rehearses every Monday at the Little Wild Goose Pagoda, built in the year 709. Xi’an had 40 orchestras playing Tang court music in 1950. Today, there are still 12 playing regularly.

Li says that the music of the Tang court absorbed cultural influences from the West. “A valuable flower once came overland from Europe via the Silk Road. It was called the tulip,” Li says. “China’s emperor saw this as an event worth commemorating, and so he had his court musicians compose a tune called The Tulip.“

The orchestras include stringed instruments such as the pipa, which looks like a lute. Wind instruments include the sheng, which has a mouthpiece connected to a cluster of bamboo pipes, while percussion instruments include the double-cloud gongs, an array of small bronze discs hanging on a wooden rack.

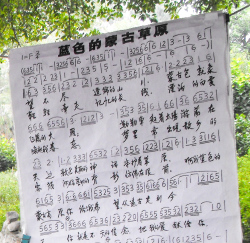

Eventually, however, by 1900, a numeric system of notation, most likely adapted from a French ‘Galin-Paris-Cheve’ system, gained widespread acceptance in China. This ‘jianpu’ notation uses a movable ‘doh’ system, with the numbers 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 standing for doh, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti. Many symbols from Western standard notation, such as bar lines, time signatures, accidentals, tie and slur, and the expression markings are also used.

I had occasion to witness this in Westlake Park, in Fuzhou. The Chinese, especially the elderly, often congregate in parks and open places to sing as well as dress up and dance. One day we were pressed to join in, whilst passing by, when we happened to hear the choir singing the old Chinese folk song, Mo Li Hua. We all made music as only people who love such things can and spent an enjoyable afternoon getting to know their methods as they asked, with sign language, about ours.

Music is innate in all peoples and is a wonderful way to learn of each other’s culture and lifestyle. What a pity the world’s leaders don’t try it too!

– Teri France (Hibiscus Coast Branch of the NZCFS)