THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION THROUGH ENGLISH EYES – DR ROSE KERR SPEAKS TO NZCFS NELSON

Review by Christine Ward

Dr Rose Kerr is an international expert in traditional Chinese arts. She is an Honorary Associate of the Needham Research Institute in Cambridge and retired keeper of the Far Eastern Department at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Her special interest in Chinese ceramics has led to Rose being made an honorary citizen of Jingdezhen, in Jiangxi Province, famous for its 1,700-year history of porcelain production. As an originator of, and contributor to, a huge range of publications and leader of many arts tours within China, Rose continues to share her lifetime fascination with Chinese arts on the international stage.

Rose and husband Steve now live in Nelson each summer. At the November 2016 meeting of NZCFS Nelson, over 50 people greatly appreciated Rose’s presentation of her student year in Beijing, 40 years ago. Here is a summary of those personal memories and insights of that time in 20th century China

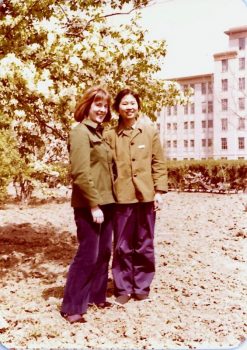

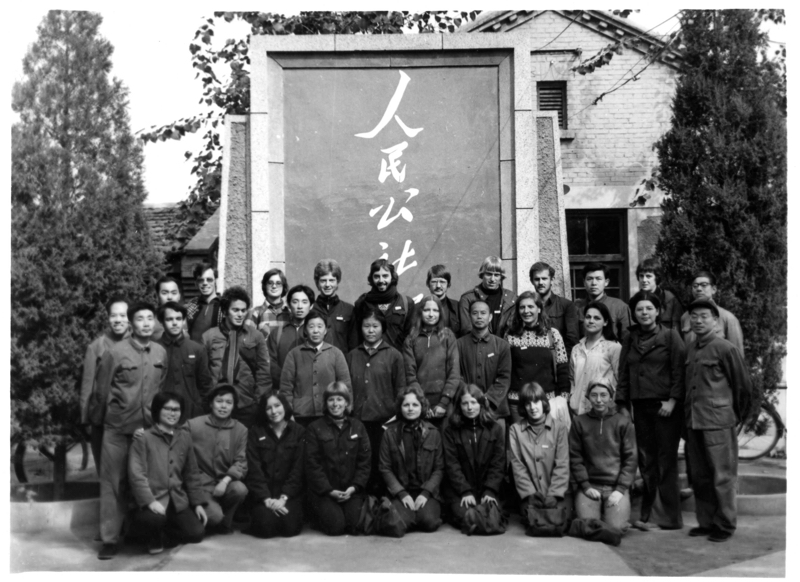

In 1975, Rose Kerr was one of a party of 12 students selected by the British Council to spend a year in Beijing to study Chinese language and culture. They arrived in Beijing for the beginning of the academic year in September and began classes at Renmin University the next day along with students from a range of Asian, African and European countries. It was only in hindsight they realised that they were there during the huge ‘social experiment’ which became known as ‘The Cultural Revolution’ [See Editor’s note, below].

Although she had studied Chinese in London for several years, Rose at first found the language lessons difficult, as old-style teaching [learning by rote] was used and few concessions were made. However, after two or three weeks, something ‘clicked’ and enjoyment began. A huge amount of valuable knowledge and understanding came, not from the formal lessons, but from sharing time with her Chinese room-mate, a clever hard-working student from a poor family in Anhui Province. They ‘talked about anything and everything’. There were expeditions arranged by the Institute, but Rose also used her free times to observe Beijing on her bicycle, ‘The Flying Pigeon‘. The Forbidden City was open and free, and it was during many visits there that her life-time fascination with Chinese traditional arts originated.

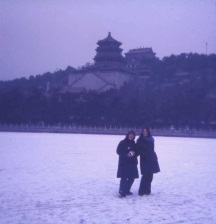

Rose has strong memories of the extreme cold from mid-November to mid-March when layers of clothing, topped by a padded cotton coat, padded gloves, padded cotton over-shoes, earmuffs and face masks were needed. There were many power-cuts and a maximum of three hours of hot water on the campus. Meals were basic with meat and grains rationed by ticket in the student canteen. Only Sunday was lesson-free, although Wednesday afternoon was given over to tidying the campus or military training. The latter included marching drills and practising throwing hand grenades!

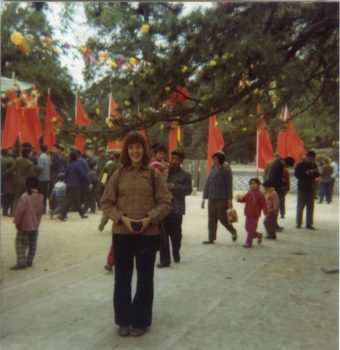

In January 1976, the foreign students were taken to Zhou En Lai’s funeral, and placed in front rows, perhaps to establish an international presence. Thus Rose could join in filing past, (and photographing) the premier’s coffin, and shaking the hand of his widow. She also attended colourful celebrations and parades for National Day, Spring Festival and May First.

A significant part of the year was three sessions of ‘open-door-schooling‘, with students and teachers working in re-education programmes [urban workers had to learn how the country peasants lived and worked] which were widespread during those years. Rose’s first deployment was to a rural piggery where she was involved with cabbages rather than pigs. It was very hard work and students and teachers were viewed by the peasants as being quite ‘hopeless’. There were bonuses, however, as the commune farmers were jolly and friendly. There were extra rations for the workers, and there were entertaining evening activities. Rose’s second session of ‘open-door schooling’ was carding wool at a wool factory which she did not enjoy. Finally she worked at the ‘East Winds Market’, selling apples and oranges at a fruit stall, where the foreign students became famous for their bumbling attempts to tie up single pieces of fruit in little squares of paper.

After the university year ended, there were some special programmes arranged for the foreign students to fill in their year to the end of August. The summer heat had already set in when, on July 28, Rose and other foreign students, were celebrating with pancakes, caviar and lots of vodka. After cycling back to the Institute, she fell into bed, rather worse for wear, wearing very little due to the heat. Then, at 4 am, the Great Tangshan Earthquake struck, force 7.8 at a depth of 7.5 km, with a death toll possibly reaching 650,000. Although the epicentre was 140 kms away, there was a great deal of damage and terror in Beijing. Rose managed to put on a light wrap before rushing down the rocking stairs and huddling with many naked people in a courtyard as the many aftershocks rolled in. The foreign students were evacuated by train to Xi’an for a couple of weeks, and then returned briefly to Beijing to be repatriated. Rose decided to extend her experience by returning home via the Trans-Mongolian railway, Russia and East Germany, providing an unexpected but fascinating ending to her year in China.

In retrospect, Rose says she learned many life lessons during this time as well as beginning her life-time appreciation of Chinese traditional arts. She admits, however, that she did not have much comprehension of what was going on politically. She took part in parades and slogans and military training, without knowing what it was all about. She suspects that many Chinese people were also lacking understanding or wider-view awareness of what was happening during those tumultuous years.

Photos from Rose Kerr’s Kodak Instamatic camera, 1975-76.

– Christine Ward (Past President of NZCFS Nelson Branch)

Editor’s notes:

The Cultural Revolution, formally the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was started by Mao Zedong in 1966. He officially declared the Cultural Revolution to have ended in 1969, but its active phase lasted until the death of the military leader Lin Biao in 1971. After Mao’s death and the arrest of the Gang of Four in 1976, reformers led by Deng Xiaoping gradually began to dismantle the Maoist policies associated with the Cultural Revolution. (Extract from the Wikipedia article Cultural Revolution.)

Dr Rose Kerr has led tours to Jingdezhen.