In 1602 Queen Elizabeth I wrote a letter to the Emperor of Cathay [China] seeking trade with China – intending for the letter to be delivered that same year. The letter never made it to China until 1984.

The following article submitted by Duncan France, Past President of the New Zealand China Friendship Society’s Hibiscus Coast Branch, sets this letter in its historical context.

When I was a lad, I remember my father showing me a beautifully illuminated Elizabethan charter. At the time he was County Archivist for Lancashire, England, and as far as I can remember the ‘Charter’ had been found by a Lancashire farmer when his bran bin had collapsed, revealing its lining! The Charter is on parchment, which perhaps explains its survival.

The Charter is, in fact, a letter from Queen Elizabeth I to the Emperor of Cathay [China] seeking trade with China and, incidentally, asking for good treatment of George Waymouth (or Weymouth), the captain of two small ships, sponsored by the East India Company, which set out from Ratcliff, England, May 2, 1602, to search for the North West Passage and thus a shortcut to China. The Elizabeth I letter, to be delivered by George Waymouth, was accompanied by contemporary translations of the letter, in Latin, Spanish and Italian, presumably so that, if no-one at the Emperor’s court could read English, then perhaps they could read one of these alternative languages.

Finally the letter was delivered:

George Waymouth never made it to China of course, but the letter was eventually delivered, somewhat late, in 1984. That year marked the 60th Anniversary of the establishment of the first National Archive of China. A colloquium was held in Beijing to mark the occasion. One of the attendees was Dr Geoffrey Martin, then Keeper of the Public Records – Britain’s most senior archivist at the time. On his arrival , Dr Martin was pleased to hand over a coloured photograph of the letter to the Director of the State Archive in Beijing.

Below is the full letter in modern English:

Elizabeth, by the grace of God, Queen of England, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith to the great, mighty and invincible Emperor of Cathay, greetings.

We have received divers and sundry reports both by our own subjects and others, who have visited some parts of Your Majesty’s empire. They have told us of your greatness and your kind usage of strangers, who come to your kingdom with merchandise to trade.

This has encouraged us to find a shorter route by sea from us to your country than the usual course that involves encompassing the greatest part of the world.

This nearer passage may provide opportunity for trade between the subjects of both our countries and also amity may grow between us, due to the navigation of a closer route. With this in mind, we have many times in the past encouraged some of our pioneering subjects to find this nearer passage through the north. Some of their ships didn’t return again and nothing was ever heard of them, presumably because of frozen seas and intolerable cold.

However, we wish to try again and have prepared and set forth two small ships under the direction of our subject, George Waymouth, employed as principal pilot for his knowledge and experience in navigation.

We hope your Majesty will look kindly on them and give them encouragement to make this new discovered passage, which hitherto has not been frequented or known as a usual trade route.

By this means our countries can exchange commodities for our mutual benefit and as a result, friendship may grow.

We decided for this first passage not to burden your Majesty with great quantities of commodities as the ships were venturing on a previously unknown route and would need such necessities as required for their discovery.

It may please your Majesty to observe, on the ships, samples available from our country of many diverse materials which we can supply most amply and may it please your Majesty to enquire of the said George Waymouth what may be supplied by the next fleet.

In the meantime, we commend Your Majesty to the protection of the Eternal God, who providence guides and follows all kings and kingdoms. From our Royal Palace of Greenwich, the fourth of May anno Domini 1602 and of our reign 44.

Elizabeth R

For the complete text in Elizabethan English (and an image of the seal), click here.

George Waymouth (c. 1585-c. 1612) was a native of Cockington, Devon, from a family of shipbuilders and spent his youth studying shipbuilding and mathematics. Portugal and Holland had command of the normal trade routes and the race was on to find an alternative route to the East.

George, with 35 men in two pinnaces, Discovery (70 ton) and God Speed (60 ton), set sail from London on 2nd May, 1602 with provisions for just 18 months. On 28 June, they sighted land at 62° 30′ N latitude (southern Baffin Island) but were forced offshore by fog. Throughout the journey, bad weather and then a mutiny dogged the expedition. On 26 July, Waymouth passed by the Hudson Strait, but was unable to enter and after exploring part of the Labrador Coast, headed home reaching Dartmouth on 5 September, 1602.

Presumably, George Waymouth brought Queen Elizabeth’s letter, and the translations, back with him, and somehow they ended up in the Lancashire farm’s bran bin, but just how is a mystery. These documents belonged to the Crosse family and were sent to the Lancashire County Record Office, where they are available for anyone to see and are among the most popular items.

The North West passage, a sea route through the Arctic Ocean, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, was attempted several times during the following centuries without success. It was finally navigated by Roald Amundsen in 1903–1906.

As for the Emperor of ‘Cathay’ (North China) at the time, this was Emperor Wan Li of the Ming Dynasty who had virtually become a recluse from political life. So perhaps he would not have met George Waymouth even if the captain had been successful!

Here are a few of the intriguing questions about this story:

- How did such an impressive, important document end up lining a bran bin in Lancashire?

- Why did Elizabeth I send her envoy via the most dangerous albeit potentially shorter route to China?

- How did Elizabeth hear of the Emperor of Cathay?

- How did George Weymouth know of the ‘North West Passage’?

The first question is impossible to answer. However, it would suggest that the undelivered letter might have then been considered only good enough for use as a bin liner! It is equally difficult to say how it got finally to Lancashire.

The second question is more easily answered. At that time the Portuguese had already established a trading port, Macau, in Southern China and the Dutch had established a significant footing in Indonesia and the Philippines, effectively blocked the passage of the small English fleet by the obvious route via India and the Malacca Strait (between Malay Peninsula and Sumatra). It seems likely that Elizabeth wished her envoy to steal a march on the Portuguese and the Dutch by arriving from a completely unexpected direction, without confronting either of these two nations.

Then there is the important question: how did Elizabeth know of the Emperor of Cathay?

As can be seen from the details below of Western travellers to China and SE Asia before 1600, the Court of Elizabeth could easily have heard of the Court of Cathay – either from the accounts of the experiences of Marco Polo, which were available in English in 1579 [Translated into English by John Frampton (1579): The most noble and famous travels of Marco Polo.] or from the English merchant Ralph Fitch who travelled to Malacca, which was easily within China’s trading zone at the time, and who returned to England in 1591. [Fitch’s journey is referred to indirectly by William Shakespeare in Act 1, Scene 3 of Macbeth, where the first witch cackles about a sailor’s wife: “Her husband’s to Aleppo gone, master of the Tyger.”].

Fitch became one of the most celebrated Elizabethan adventurers and his experience was greatly valued by the founders of the East India Company, who consulted him on Indian affairs.

Other pre-1600 Contacts with China:

1271-1295

Second trip of Niccolò and Maffeo Polo to China. This time with Marco, Niccolo’s son, who would write a colourful account of their experiences – well-known as ‘The Travels of Marco Polo’.

1275-1289 & 1289-1328

John of Montecorvino (1246–1328) was a Franciscan missionary, traveller and statesman, founder of the earliest Roman Catholic missions in China. and archbishop of Peking and Patriarch of the Orient.

1318-1329

Travels of the Franciscan monk Odoric of Pordenone via India and the Malay Peninsula to China where he stayed in Dadu (present day Beijing) for approximately three years before returning to Italy overland through Central Asia.

1338-1353

Giovanni de’ Marignolli, one of four chief envoys sent by Pope Benedict XII to Peking.

1420-1436

Travels of Niccolò Da Conti to India and Southeast Asia.

1549, 1552

Jesuit missionary, Francis Xavier, visited Canton in 1549 and 1552.

1583-1591

The English merchant Ralph Fitch travelled via the Levant and Mesopotamia to India and Malacca (in Malaysia).

The above contacts are an extract from Wikipedia article: Chronology of European exploration of Asia.

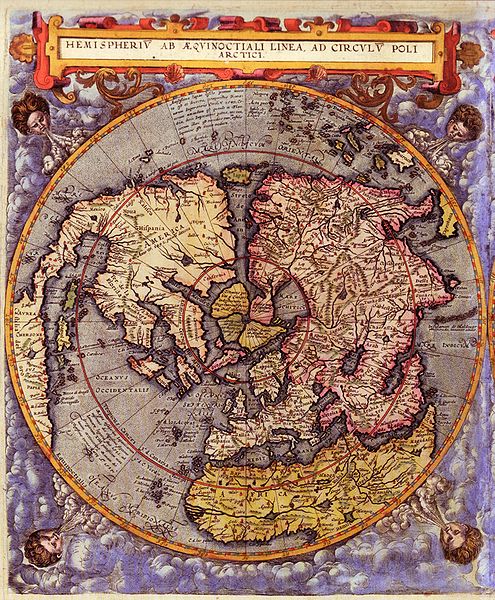

Regarding knowledge of the Northwest Passage at the time, perhaps George Weymouth knew John Davis, whose voyage to find the Northwest Passage was funded by Wallsingham, Elizabeth I’s secretary in 1583. Perhaps he had also seen a map of the Northern Hemisphere (see below) which shows a clear-run Northwest Passage, by Gerard de Jode, published in Antwerp 1593.

I acknowledge the help of the County Record Office of Lancashire in providing the image of the Elizabeth I letter + translations into 3 languages. Their reference for the letter, etc, which are part of the Crosse of Shaw Hill papers, is: DDSH 15/3.

The image of Gerard de Jode’s map is from Wikipedia Commons. See the same for more information on the image.

Duncan France