In 1938, the Chinese Industrial Co-operatives (Indusco) movement was set up by Rewi Alley, Nym Wales and Edgar Snow. It was introduced to help the people of Free China work for the war effort and be educated to survive during the catastrophic war with the Japanese and is still in operation today under the name of ICCIC (see below).

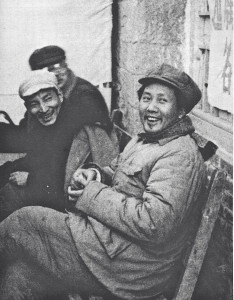

In 1981, Edgar Snow’s wife, Lois Wheeler Snow, produced a book “Edgar Snow’s China” about her husband’s long time personal involvement with that country. With more than 450 photographs, it is a matchless record of a central event of our time and some of these fascinating pictures are produced below.

NZCFS acknowledges Lois Wheeler Snow’s kind permission (in 2014) for use of images and text from her book ‘Edgar Snow’s China‘, 1981, Random House NY, ISBN 0-394-50954.

Below are Edgar Snow’s comments from the book, on the ‘Gung Ho or Indusco’ movement, as well as his recollection of Rewi Alley.

“Among non-party patriots of all descriptions, real faith persisted that a progressive government representative of varied opinion and worthy of the people’s spirit of devotion and self-sacrifice would emerge during the war. Out of such faith grew the most original and hopeful experiment of the ’united front’ period – the Chinese Industrial Co-operative organisation (Gung Ho, or the Work-Together Movement, Indusco). It provided work and an education for tens of thousands of Chinese and proved indeed to be the forerunner of what ultimately became the largest producers’ co-operative movement in the world.

“I vividly remember the setting in which the idea was born. The war had passed from Shanghai on the Yangtze River Valley. Behind it lay the ruins of a nation’s industry. Except for the tiny oasis of the International Settlement, everything for miles seemed a desert of rubble, charred timbers and twisted iron, beneath which many bodies still lay. Over 70 per cent of China’s pre-war industry was concentrated in a little triangle bounded by Shanghai, Wushi [Wuxi] and Hangchow [Hangzhou]. By early January 1938, all that plant had fallen to the Japanese, for whom the immobilization of China’s industry and labour was a main objective of “total aggression”.

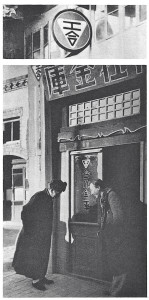

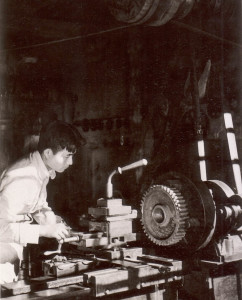

“Indusco set up several hundred small factories, workshops, power plants, transports and mines. We had our own training schools, war veterans and war orphans vocational centres, printing and publishing houses, lunch rooms, clinics, nursery schools and character-study schools for illiterate worker-members and their children. Indusco became a reasonably sound prototype of a democratic, co-operative society, producing a wide variety of goods of war value. Some mobile co-operative units functioned far behind the Japanese lines in North China.

“Indusco – as the movement was known abroad – was primarily the invention of Rewi Alley, Nym Wales and myself.

“It could never have got off the ground without the initial sponsorship of a strange pair of enthusiasts – Soong Chin-ling [Song Qingling] and the British ambassador in China, Sir Archibald Clark-Kerr, later to be Lord Inverchapel.

“He personally presented the Indusco scheme to the Generalissimo and Mme. Chiang Kai-shek and H. H. Kung. They agreed to try it out. He also secured the release of Rewi Alley by the Shanghai Municipal Council and Chiang appointed him to carry out the plan. Alley knew written and spoken Chinese, and had wide technical knowledge as well as broad experience in China. He was appointed chief technical adviser and quickly gathered together a field staff of able and honest young men. He set up an organisation based on modified co-operative principles that provided for low interest loans and private credits to finance the first co-op units, with workers entitled to buy over their shares and take full control as soon as they became technically trained to do so.

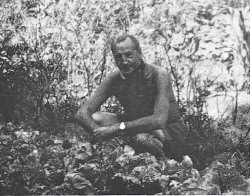

“I first met Rewi far up in Inner Mongolia in the arid June of 1929. Employed at the time as a factory inspector by the Shanghai International Settlement, he had chosen to spend his annual vacation in the famine region with a handful of foreigners who ran a few soup kitchens and were offering food and shelter to those still capable of working on the irrigation canal near Kueisui. He was a strangely out-of-place figure in that dark sickly crowd, his sunburned face covered with dust beneath a fiery bush of upstanding hair. When he stood with those giant’s legs spread apart in a characteristic attitude, he seemed somehow rooted to earth.

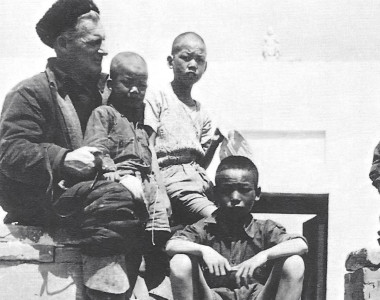

“That summer, Alley adopted his first Chinese orphan, a boy he picked up among the human debris of the famine and took to Shanghai to be educated. Two years later, Alley was loaned by the Shanghai Municipal Council to help rebuild the Yangtze dikes after the great flood. Again he came out with a famine orphan. In Municipal Council circles, where few white sahibs would dream of sitting down with a ‘coolie’ at their table, the Family Alley soon became a kind of legend.

“Alley was, of course, only the ‘prime mover’ that had started the wheels. He and the unique backing he had were necessary guarantees to Chinese members that the organisation would have a chance to develop along true co-operative lines free from the traditional incubuses of bureaucracy, nepotism and graft. Thus reassured, some of China’s ablest engineers and technical men had given up highly paid jobs and volunteered for the new industrial army, with an enthusiasm that amazed cynical onlookers.

“Virtually free of graft and nepotism, the organisation was for a time relatively immune from bureaucratic control. That very circumstance, a historical accident, was soon to mark Indusco as a target for destruction by the most reactionary elements in the regime it might have helped to save.

“Ironically, it was the Communists themselves who would see the usefulness of the co-operative method of organising the people, for their own ends, in a great transitional stage of the consolidation of their revolutionary power.

“By 1942 the Yenan [Yan’an] depot came to be much the largest regional headquarters in the country with as many workers as all the others in China combined.

“No Westerner since Marco Polo has so profoundly influenced our attitudes toward China as the late Edgar Snow. Not only was he the foremost eyewitness chronicler of the Chinese Revolution, he was the one American whom the Communist leadership trusted. Edgar Snow’s China is a first-hand account of that revolution, compiled from his writings by his widow, Lois Wheeler Snow.

‘When he arrived in China in the late 1920s [1928], he encountered a people crippled by their backwardness and shackled to a corrupt and feudalistic government. Fascinated and moved by what he saw, Snow would remain in China for more than a decade. In 1936, he ventured into the forbidden interior of the county to seek out the legendary leaders of the outlawed Communist Party – so-called ‘Red Bandits’ who had enormous prices on their heads. Snow found a ragged army of guerrillas living in caves, men and women who had just completed one of the epic treks of history, the Long March. He would form life-long friendships with people like Mao Tse-tung and Chou En-lai. Years later, a hint dropped to him by Chairman Mao led to President Nixon’s visit to Peking. This book covers the tumultuous events of the years he lived in China from the late 1920s when the Communists went underground, until their victory in 1949.”

ICCIC still manages democratic co-operatives in various parts of China. The New Zealand China Friendship Society (NZCFS) supports this movement both materially and morally as one of its major projects.

NZCFS has initiated many projects for the Gung Ho Co-operative scheme:

For example, after the Sichuan earthquake, NZCFS executive members Dave Bromwich and Sally Russell developed two projects to assist the people – the first project being to help with a farmers’ irrigation channel repairs in Huang and the second to provide training to enhance co-operative structures after the earthquake.

Many more examples can be found in the “Gung Ho Co-operatives” article on the NZCFS website .