NEXT MEETING:

We have the historic documentary Inside Red China(1957) on restricted loan from the New Zealand Film Archive and this is our only chance to see it.

In 1957, the Chinese People’s Association for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries invited NZ China Friendship Society President and poet R.A.K Mason and others to visit China. Film makers and members Rudall and Ramai Hayward were part of the group and made a documentary film Inside Red China, that includes Ramai gifting a cloak from the Maori King Koroki to Chairman Mao Zedong. In 1958, the documentary screened before Rank feature films in cinemas around the country and was subsequently acquired by the Department of Education for use in schools.

The film ends with the question: ‘What will China be like in 50 years time?” We will screen Inside Red China and then New China in Her First 60 years (2009), providing some answers to the question. Total viewing time one hour.

Note: Mao’s feather cloak is a precious Maori taonga on loan to Te Papa and is on display from 13 June to 20 October 2013.

Date: 5 July 2013

Time: 7.30pm

Where: Hastings District Council Chambers in Lyndon Road.

Last Meeting

Thank you Janet Kee and Hong for preparing the Chinese ‘hot pot’ 火锅 or ‘steamboat’. You can make this in any portable cooking device and its simple, delicious and good fun where everyone has a hand in the cooking.

Janet used a Sichuan broth but any stock is great as the base. Heat it up and keep to a low simmer. Then you add the ingredients a few at a time to keep the temperature high. After a few minutes or less the ingredients can be removed and eaten. Janet had a dipping sauce of sesame (like tahini) and soy. The broth becomes more and more tasty and can be eaten as a soup at the end of the meal.

Look at our facebook page to see more photos of this evening

Look at our facebook page to see more photos of this evening

Education Link Group Update

Sue Padfield, Chair of the Education Link Group sub-committee of the Hastings District Council International Advisory Group and a Hawke’s Bay NZCFS Branch committee member reports that:

“The Education Link Group is delighted to announce that two students from Guilin will be arriving in July. They are the first recipients of the generous Nova Lowe Bequest, which provides for students from Guilin to come to Hastings. This bequest has enabled two excellent candidates (one boy, one girl) to be chosen according to the criteria. They are students who would not normally be able to afford the opportunity to study here, but have a good academic record and outgoing personalities. We hope they will be the first of many more to come.

They will be home hosted with Hastings Girls High and Havelock North High School pupils, who will return later in the year to be hosted by these students families. Credit must go to Geraldine Travers, Principal of Hastings Girls High, who has been working on this for some years and has managed to get the international school fees waived for these students, as this is an exchange. The visits of teachers to and from Guilin has also created a strong bond with our Sister School, and Guilin Foreign Affairs Office is always supportive. We hope they enjoy their stay and build a bridge with their hosts to last many years.”

News from the Internet

The Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA) was founded in 1976 to promote and support the study of Asia in Australia. Their electronic newsletter Asian Currents aims to connect Australia’s academic experts on Asia with journalists, policy makers, business people, artists and other educators. By telling you what is happening in the research world, we hope you will be able to make better use of the wealth of knowledge available and that you will recognize the importance of fostering Australia’s Asia knowledge. Electronic subscriptions are free of charge: Subscribe to Asian Currents

Extracts from the June 2013 issue of “Asian Currents”:

The emptiness at the heart of Xi Jinping’s China Dream

The realization of Xi Jinping’s China Dream is bedeviled by paradoxes.

By Gerry Groot, Head of Discipline and Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies

at the Centre for Asian Studies, University of Adelaide.

One of the key ways Xi Jinping, the new General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and therefore also the new Chinese President, has already made a dramatic mark on his party, country and the world, has been to announce a China Dream as a rallying point, inspiration and a basis for a renewed form of patriotism.

To understand why a generally embraced China Dream would be extremely useful to the CCP we need only to think of some of the paradoxes currently bedeviling it. In today’s China, many people are buying infant milk powder for their infants from smugglers because they have so little trust in the ability of the Party-state to ensure adequate regulation, inspection and enforcement that is not subject to corruption. On the other hand, there is precious little faith that fellow citizens won’t resort to dangerous and immoral ways of making money, including being prepared to adulterate even infant milk powder with kidney-destroying melamine plastic simply to fake the protein readings. Cardboard in dumplings and gutter oil in cooking among many other scandals related to foods and medicines, only add a growing sense of insecurity and mistrust.

Yet, another paradox is that, based on opinion polls by reputable foreign firms, some levels of trust in the central government in Beijing are actually much higher than in Western democracies.

Today, one consequence of the absence of independent institutions is endemic and apparently growing levels of corruption at all levels of society. Kindergarten teachers are bribed to try to get good results in order to allow ‘Xiao Li’ access to a ‘good’ primary school. Top leaders of the Party-state’s inspection services themselves have been found out. The latter are (very) occasionally executed, the former almost never punished. As in empires of old, even positions in government and the military are again being bought and sold, with women having to pay a premium to overcome the disadvantage of their sex.

The general reaction of the CCP leadership is not to spend too much time trying to address the systemic contradictions within its own organisations, systems of rewards, promotions and punishments but to resort to a pre-modern insistence that moral education be stepped up. This will, they maintain, compensate for the problems of modernity, the weaknesses of individuals and what it prefers to see as deliberate efforts by ‘hostile Western forces’ to undermine China through peaceful evolution and promotion of ideas like universal human rights and democracy. Its reaction to protests against systemic problems in the wake of the bloody suppression of the student movement of 1989 was, in 1990–91, to launch the Patriotic Education Movement (Aiguo zhuyi jiaoyü yundong) for every young Chinese, from kindergarten onwards. Part of this includes instilling a personalised sense of humiliation on behalf of China, for defeats of the Qing Empire, beginning with the Opium Wars of the mid-19th century, and the ‘unequal treaties’ that the Qing acquiesced to. This education also allowed some leeway for young Chinese to identify with ‘China’ even if they were not predisposed to the CCP itself.

This renewed version of the ‘Century of Humiliation’ theme, though, has now become both an encouragement to those wanting China to be assertive in the world and claim what they see as rightfully Chinese territories (such as in the South China Sea), and a significant impediment to the CCP’s ability to conduct foreign affairs. Anything less than the full capitulation of other parties to Chinese claims are now readily seen by many raised on patriotic education as more signs of weakness in the face of foreign aggression and injustice.

With the rise of the internet generation and increased social space, there are more voices influencing even foreign policy, but through very narrow lenses. Even though the CCP created these lenses and largely shaped the understanding of what China and her national interests are, it now finds itself painted into a corner by some aspects of its success. It has created a very narrow statist nationalism that, while usually pleasing at home, is a real problem abroad.

More importantly, it is not fully within Party control but is harnessed to deep emotions like humiliation which can be very difficult to rein in. The China Dream could be a way around this narrowness by providing a broader base of principles around which to rally all Chinese, at home and hopefully, abroad. It is also clearly a reaction to internal demands that China solve problems like corruption by adopting more Western principles and fully accepting Western conceptions of universal rights. Moreover, China’s economic success would in itself perhaps turn these dreams into counter universal values.

Yet however attractive this idea of counter values is, where can they be found and how can they be propagated? The China Dream demands powerful ideas and principles which will support current statist nationalism but which will also be a counterbalance to them. They will be able to counter Western ideas and even be as attractive, if not more so! But where will they be found? What can be mined from Buddhism, assuming it is accepted as being authentically Chinese, or Daoism or Confucianism? Christianity and Islam, by definition, are too foreign to even consider. The mere fact that nothing jumps out is an indication of the difficult task Xi has set China’s theoreticians and researchers.

For the full article go to: http://www.asaa.asn.au/publications/ac/2013/asian-currents-13-06.pdf

China Book Review by Matthew Griffiths

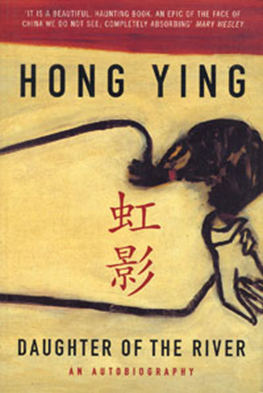

‘Daughter of the River, An Autobiography’, by

Hong Ying (Bloomsbury, 1999)

Stories of growing up in China are becoming more and more common. Wild Swans by Jung Chang may be the best known of them all with many others having followed. Daughter of the River deals with a different strata of society. The intricacies of party politics and personal feuds and the ups and downs of the cultural revolution that are the core of Wild Swans are not to be found here.

Instead Daughter of the River traces the life of a girl growing up in a hillside slum in Chongqing, on the Yangtze River. Born in 1962 during the famine induced by Mao’s ‘great leap forward’, she survives by the efforts of her mother and lives through the Cultural Revolution before coming of age in the post-Mao era.

As a child she felt her life was full of mystery, unsure why she was somehow different, why she seemed to be watched. Her parents were poor, her father worked on the boats that ply the Yangtze River, her mother a manual labourer struggling with the physical demands of her work and the hardships and life and death decisions in bringing up six children in extremely difficult times. Hong Ying’s own life is miserable and bright spots are few and fleeting. She hates her mother while her father, now blind, treats her well.

The grim struggles of her family to survive are mirrored in the difficult lives of others around her – a kind teacher with a past, her relatives, classmates and workmates. The book brings to life the human impacts of the stresses, violence and tragedies brought on by misguided polices and harsh rule of the Chinese government. Even after it was over, the Cultural Revolution continued to blight lives.

The author finds an outlet in writing and eventually a path opens to leave Chongqing. But even then life does not go smoothly; “following the river downstream” she finds herself in Beijing in 1989 during the events in Tian’anmen Square.

The horrors of the times are related in a sombre low-key style which only serves to emphasise the subject matter. This book is not for the faint-hearted but is well worth reading for another view of real life in China.

Daughter of the River is available from the Napier Public Library. Hong Ying has also written some fiction woks which have been translated into English, including K: the art of love (Hastings Library) and Peacock cries at the three gorges (Napier Library).

[Note: Matthew Griffiths is a long-time member of the New Zealand China Friendship Society. He loves Chinese food, has visited China many times, studied Mandarin, and attempted to learn Tai chi. He and his Chinese-born wife Deborah have two bilingual children and they lived in China from 2008 to 2010 and he still can’t get enough. Editor]